It’s a known fact: People trust customer reviews more than they do critics. As one influencer posted recently on Review Trackers — not exactly an unbiased source, as any objective, professional journalist worth their salt, would point out — “So it’s between the New York Times and Yelp.”

The academia website academia.edu recently asked — somewhat rhetorically — if consumer critics write differently from professional critics, while the self-explanatory site “Coaching for Leaders” (coachingforleaders.com) named “3 Differences Between Feedback and Criticism” (the Dale Carnegie principle: ‘Don’t criticize, condemn or complain’).

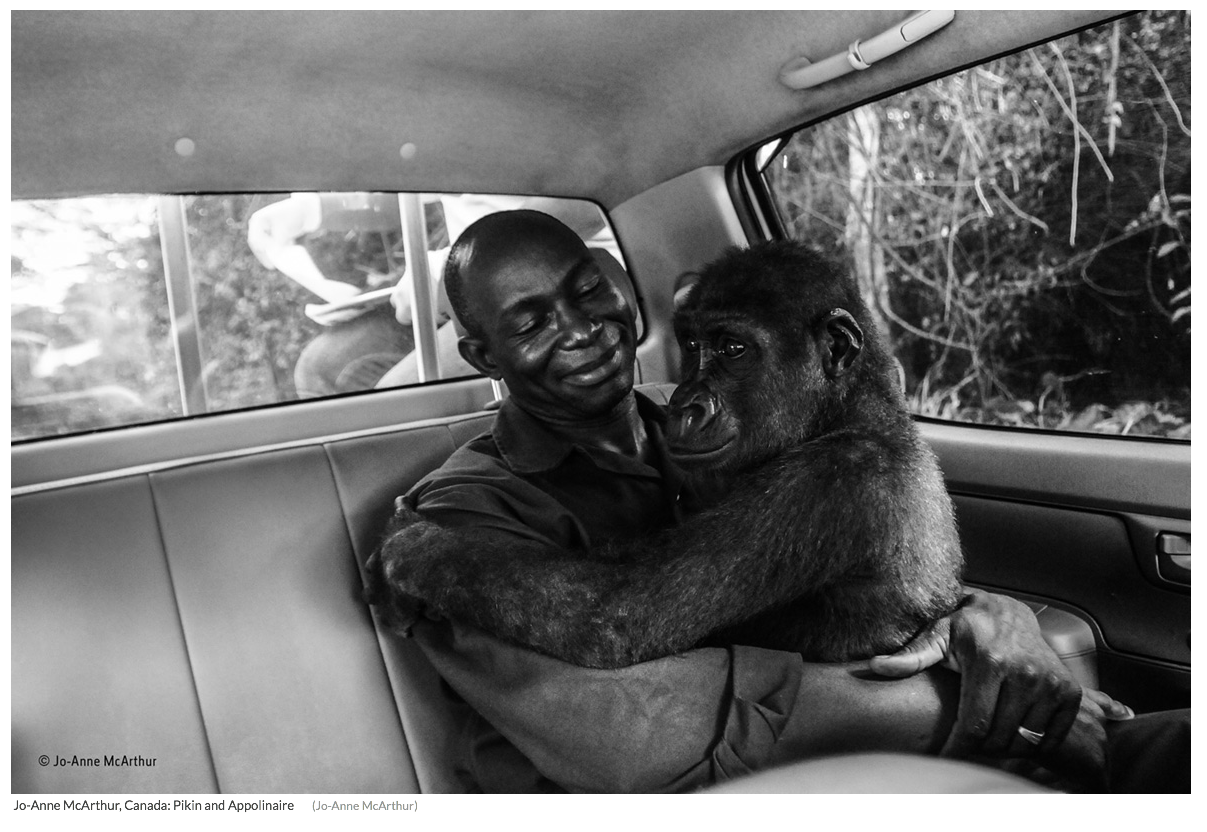

All of which is a roundabout way of taking a second look at the 54th annual Wildlife Photographer of the Year awards, announced just last week.

I was fairly critical — and I stand by my criticism — of the judging committee’s choice for the top image this year, which favoured the safe and comfortable over last year’s daring and, some would say, controversial and inappropriate choice of a poached rhino, slaughtered for its horn, worth an estimated USD $120,000 on today’s black market. (Why ground powder from rhino horn, made of the same material — keratin — as our fingernails, should be so valuable to a primarily Asian market, and it is strictly an Asian market we’re talking about here, is a topic for a whole other debate.) One idea holds that wildlife photography awards should celebrate the beauty of nature; the other holds that, in the environmental catastrophe facing humankind and planet Earth today, the top award is better suited as a deliberate provocation, urging us to wake up and shake us out of our complacency.

Any award calling itself “the People’s Choice” wears its intention clearly and on its sleeve, though. Every year, following the WPOTY’s black-tie awards dinner at London’s Natural History Museum, the “Oscars of wildlife photography awards,” as they’ve been called, the judging committee announces 24 images shortlisted for the People’s Choice Award, which is announced the following February (voting for this year’s edition closes Dec. 13). Each visitor to the Natural History Museum’s website is allowed one vote, and one vote only. (This isn’t America’s Got Talent, where you can vote early and often, in almost as many different ways as you can think of.)

Anything open to the general public is driven by emotion, not reason.

That’s positive emotion, though. One of this year’s shortlisted finalists, of a starving polar bear, went viral around the world earlier this year. It sparked a lively and at times bitter debate about humankind’s effect on climate change in the polar regions. (Climate deniers refused to accept that the melting polar caps could have anything to do with a starving polar bear, et alone that humans might be responsible.) The image, by SeaLegacy conservation photographer Justin Hofman, is undeniably powerful, and has already proved influential, but I suspect it won’t win the people’s vote. (In his caption, titled “A Polar Bear’s Struggle,” Hofman admits his entire body was pained as he witnessed the starving bear scavenge for food at an abandoned hunter’s in the Canada’s high Arctic; the bear could barely stand under its own power, Hofman recalled.)

There’s nothing wrong, in this case, with favouring beauty over fragility. Inspiration works in wondrous, often mysterious ways. In a world beset by grim, increasingly bleak news — everything from climate change and dwindling food resources to a new mass extinction — one can’t fault people for looking for a ray of light in the darkness, wherever that light may be found.

As the Natural History Museum’s own guidelines for the Lumix People’s Choice award points out, they’re looking for a winning image that “puts nature in the frame,” something that reflects the beauty and fragility of the natural world — with the emphasis, I’m guessing, on “beauty.”

A conservation-photographer acquaintance and occasional travel companion tells me he’s doubtful of people’s choice awards as a rule, since a public vote tends to favour those finalists who have a sizeable social media following, and he has a point.

Still, as someone who pays attention to customer reviews — I’ve personally known a number of professional critics, in different fields, who are so screwed up I’m not sure I’d trust their judgment of anything, let alone something I care about — I’m always curious to see where popular tastes lie.

I’ve yet to decide which image I’ll be voting for myself, but I have narrowed my choice down to three or four candidates. I have until next month to make my final decision — and you to, too, if you choose to participate.

As with any vote, though, remember: If you don’t vote, when you had the chance, you can’t complain afterwards, if the vote didn’t go the way you want.

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/visit/wpy/community/peoples-choice/2018/index.html

Wildlife Photographer of the Year is the world's most prestigious nature photography competition (WildlifePhotographerOfTheYear.com). This year’s finalists and winners, some 100 images in all, are on display at London’s Natural History Museum from now until June 30, 2019. See nhm.ac.uk/wpy for tickets.