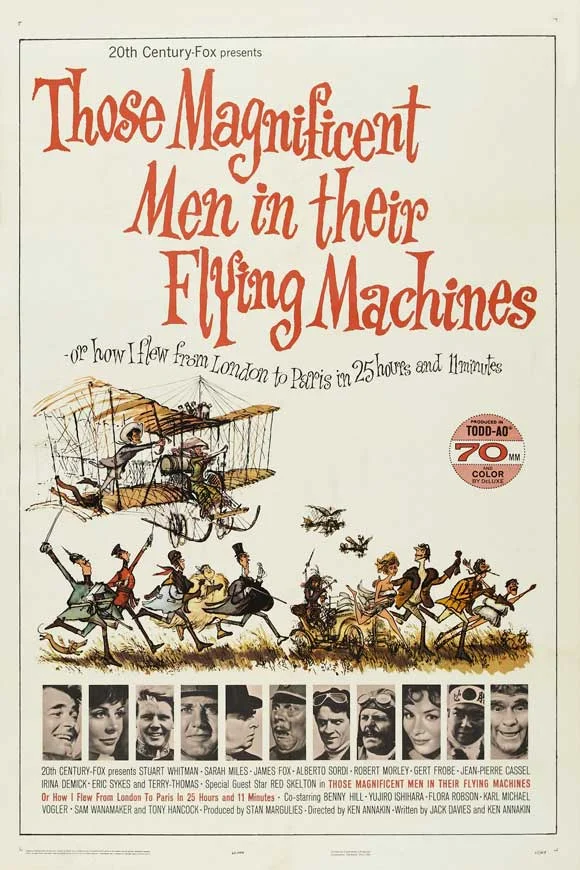

No one said it would be easy. Renowned eccentric Maurice Kirk, 71, one of the magnificent men in their magnificent flying machines making the cross-Africa trek as part of the Vintage Air Rally, in which nearly two dozen pre-1939 biplanes are flying from Crete to Cape Town, South Africa over 35 days, was reported missing over South Sudan earlier this month.

Of all the places to be reported missing in a rickety World War II-era flying machine, South Sudan is not as ideal as, say, the Hudson River.

As it happened, Kirk turned up alive and well — as an unscheduled guest of the Ethiopian state, provided free room and board in the local clink— just days later, in a dusty, flyblown outpost of the Sudan-Ethiopia border.

Perhaps Kirk’s paperwork had been in order, perhaps not. Either way, no one, it seems, bothered to give the border-post guards a heads-up, which is odd because South Sudan is, after all, a war zone. Viewed from afar, and unexpectedly, even a 1943 Piper Club plane can look suspicious.

This is Africa, as Leo DiCaprio’s character was wont to say in the 2006 movie Blood Diamond. Forget the heat, the humidity and the vicious crosswinds. Never mind the bugs, the pestilence and the dangerous animals: It’s the bureaucracy that will get you every time.

By the time the contretemps was over — “This has all been a terrible misunderstanding,” was repeated more than once — the pilots of 20-something vintage planes were allowed to continue, Ethiopian officials confirmed with the BBC, underscoring another curious fact of life in modern-day Africa: When something goes seriously wrong, it’s often down to the BBC to sort it out.

As of posting, the pilots — and their magnificent flying machines — are cooling their heels in Nairobi, before winging off, Out of Africa-style, over Mt. Kilimanjaro to Zanzibar.

The planes, dating from the 1920s and 1930s, took off from Crete on Nov. 12 on their 12,900km (8,000 mile) journey to Cape Town. The rally is an attempt in part to recreate the 1931 Imperial Airways “Africa Route.” The flying teamsare expected to reach their destination on Dec. 17, barring further unforeseen difficulties.

The teams, complete with support aircraft and helicopter supply teams, are being piloted by flying enthusiasts from a wide range of countries, including Belgium, Germany, Botswana, South Africa, the UK, Canada and Russia. The rally includes husband-and-wife teams, fathers and daughters and entire families. One young woman pilot, from Botswana, is 15.

On the other end of the age spectrum, Kirk, it goes without saying, is the quintessential eccentric Brit, complete with a spotty past — he’s a former “drinking partner” of the actor Oliver Reed, The Guardian reported — and a knack for talking himself into, and out of, trouble.

By the time the border incident was over, the grounding and detention of pilots and their planes involved both Britain’s Foreign Office and the U.S,. State Department, this after Wesenyeleh Hunegnaw, head of Ethiopia’s Civil Aviation Authority, told the Associated Press that the pilots had entered Ethiopian airspace illegally and were “under investigation.”

A spokesperson for the UK Foreign Office said simply: “We are in contact with the local authorities regarding a group who have been prevented from leaving Gambela airport, Ethiopia.”

Ah, yes, the language of international diplomacy. Gotta love it.

The magnificent men — and women — in their magnificent flying machines had to surrender their cellphones and laptops, before being waved on to neighbouring Kenya. Presumably by now, iPhones and MacBook Pros have been returned to their rightful owners, assuming, that is, that the flying teams don’t include some actual spies.

And then there are the eccentrics.

Kirk had a near miss once in France, in his pre-Vintage Air Rally flying days, when he suffered engine failure in his plane, dubbed “Liberty Girl II,” while approaching Cannes. “That so easily could have ended in a tangled pile of twisted aircraft and Maurice,” he posted on Facebook. There very nearly was not a Liberty Girl III.

Africa, it goes without saying, is, well, big.

“Where am I?” Kirk posted angrily on Facebook, on Nov. 19. “I keep getting lost which is why I really wanted to go via Gibraltar and just keep the sea on my right to Table Mountain [Cape Town].”

As it is, Kirk has already suffered a puncture and propeller failure, not to mention that unscheduled stay as a guest of Ethiopian border authorities. He very nearly got himself disinvited from the rally before it even began, owing to what rally organizers called, “a mismatch in expectations.” There have been pluses, mind. Dongola, Sudan, will be a cherished memory for life, The Guardian reported him saying. “(This is) what life is all about … the fried fish fresh out of the Nile … the coffee you can [stand] your spoon up in.”

Ethiopian coffee, no doubt.