“This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Iceland has lost its first glacier to global heating, but the small island nation is not about to let that pass unrecorded. A plaque to be installed next month at what remains of Okjökull glacier will tell future generations that all 400 of Iceland’s glaciers will meet the same fate, during the next 200 years, unless humanity found a way to reverse the effects of our growing climate crisis.

The plaque, in English and Icelandic, is titled, “A letter to the future.” Iceland is justifiably proud of its moniker “Land of Fire and Ice,” as immortalized in its other-worldly landscapes of volcanoes and glacier.

“This will be the first monument to a glacier lost to climate change anywhere in the world,” Rice University (Houston) anthropologist Cymene Howe told the news agency Reuters earlier this week. Howe and her fellow Rice researcher Dominic Boyer made a documentary film last year about Ok glacier’s, as it’s widely known, vanishing act.

“By marking Ok’s passing, we hope to draw attention to what is being lost as Earth’s glaciers expire.”

Howe and Boyer made the documentary Not Ok last year, to show how the climate emergency is already affecting ordinary people’s lives.

Shrinking glaciers have already caused profound shifts in weather patterns across the world, and not just because the Icelandic Meteorological Office says so. Even the jet-stream has been disrupted, leading to wild temperature swings this summer across both Europe and North America.

Howe’s statement, as reported by Reuters, may sound dry, as press statements tend to do, but it bears paying attention to, just the same.

“With this memorial, we want to underscore that it is up to us, the living, to collectively respond to the rapid loss of glaciers and the ongoing impacts of climate change.”

Save it or lose it, in other words.

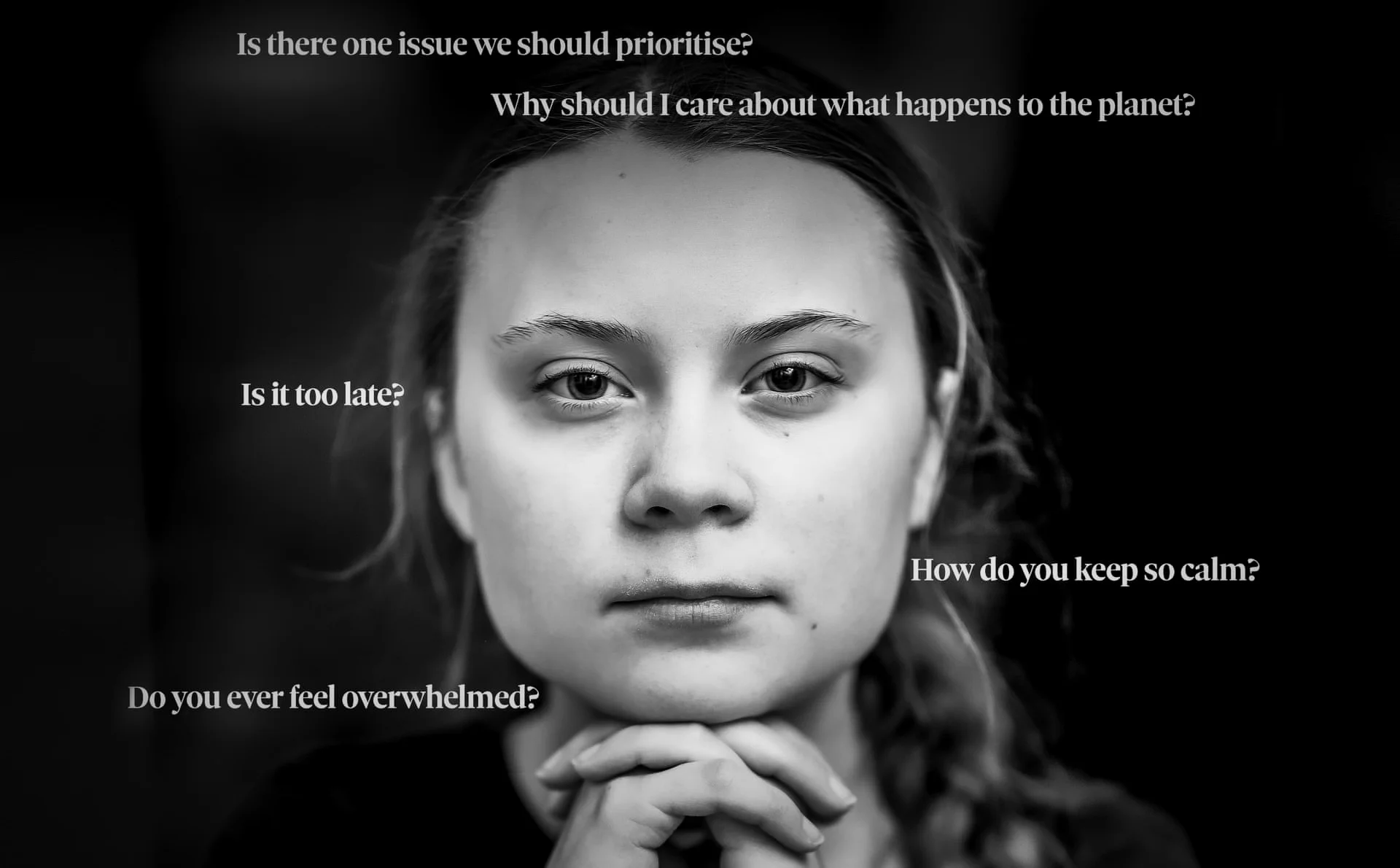

Teen activist Greta Thunberg has done her part,

lord knows, but is really down to a 16-year-old to save the planet?

Just a century ago, as the guns of August were finally growing silent following the end of the First World War, Okjökull glacier covered some 15 sq km (6 square miles) of mountainous terrain in western Iceland. The ice was 15 metres (165 ft) thick. Today Ok-Not-Ok has shrunk to barely 1 sq km of ice, and is less than 15 metres (50 ft) deep. It has lost its official status a glacier, as a result.

A glacier is officially defined as a persistent mass of compacted ice that accumulates more mass each winter than it loses through summer. Glaciers move because they shift quite literally under the force of their own weight. When this stops, the remains are known as “dead ice.”

Rice University researchers, Icelandic novelist Andri Snær Magnason and geologist Oddur Sigurõsson will unveil the plaque on Aug. 18.

The plaque will include the words 415ppm CO², a reference to the record-breaking level of 415 parts-per-million of carbon dioxide recorded in the atmosphere this past May.

The far north has been warming twice as fast as the rest or the planet, owing to physical forces that climate deniers are unlikely — or unwilling — to understand. This past June was the warmest ever recorded.

While it’s clever — if a bit precious — to point out that there have been epochs in geological time when the Earth was much warmer than it is today, that’s a specious argument. We’re living in the Anthropocene era, loosely defined as the period of time human beings have been on the planet.

If the entire history of planet Earth is recorded as a 24-hour clock, humans first emerged at 11:58:43 pm. Plants on land, for what it’s worth, first emerged at 9:52pm. The idea that a glacier as large as Okjökull can vanish in a mere 100 years should alarm everyone, even a dyed-in-the-wool climate denier.